A new survey says consumers find e-commerce sites often fail to meet expectations. Experts say that’s because shoppers have become accustomed to how Amazon gets things done to their liking.

Source link

blame

President Joe Biden speaks during an event about lowering costs for American families at the Granite State YMCA Allard Center of Goffstown on March 11, 2024 in Goffstown, New Hampshire.

Sophie Park | Getty Images News | Getty Images

President Joe Biden is starting to win the inflation blame game against corporations.

A recent Financial Times-Michigan Ross online poll found that 63% of survey respondents blame price increases over the last six months on “large corporations taking advantage of inflation,” up from 54% in November. Meanwhile, 38% of respondents attributed the price increases to Democratic policies, unchanged from November.

A 59% majority still disapproved of Biden’s handling of the economy, down only slightly from 61% in November, the poll showed. The poll, taken between Feb. 29 and March 4, surveyed 1,010 registered voters with a margin of error of +/-3.1%.

Still, voters’ growing frustration with businesses is a relief for the White House and Biden’s reelection campaign.

Both have been slogging through an uphill battle to convince Americans that stubbornly high inflation is the fault of corporations, not Bidenomics.

“Too many corporations raise their prices to pad their profits, charging you more and more for less and less,” Biden said Thursday in his State of the Union address. “That’s why we’re cracking down on corporations that engage in price gouging or deceptive pricing from food to health care to housing.”

The consumer price index released Tuesday found that inflation ticked 0.4% higher in February, mostly matching analysts’ expectations. The rise in prices was driven primarily by housing costs, one of the key focuses of Biden’s 2025 budget proposal released Monday.

“As I said in my State of the Union, we have more to do to lower costs and give the middle class a fair shot,” Biden said Tuesday in response to the CPI report.

In another welcome data point for Biden, consumer confidence has seen a record turnaround.

In February, consumer sentiment was at 76.9, roughly the same level as when Biden entered office, according to a widely watched consumer survey from the University of Michigan. That is a remarkable rebound from when consumer sentiment in the survey hit an all-time low of 50.0 in June 2022.

The Financial Times poll confirmed rosier economic attitudes. Though the majority was still more negative on the economy, the gap narrowed: 30% of respondents rated overall economic conditions as positive, a nine-point increase from November.

Biden’s battle against corporate interests has been the foundation of his economic platform since the beginning of his administration.

From an aggressive antitrust crusade to a crackdown on junk fees to new rules on drug pricing negotiation, the president has established various battlefronts to wage war against rising consumer costs. Biden’s 2025 budget also restated his demand for tax hikes on billionaires and wealthy corporations.

However, as the November general election looms, Biden’s next economic face-off is against former President Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican presidential nominee.

In a CNBC interview Monday, Trump slammed Biden’s economy and “through the roof” energy and food prices. Recent polling has found that voters still prefer Trump’s handling of the economy to Biden’s. Trump has said that if he’s elected he is considering universal import tariffs, which would likely raise consumer prices.

In the same interview, Trump suggested he was open to making cuts in Social Security, Medicaid and Medicare. The Biden campaign immediately jumped on it.

“This morning, Donald Trump said cuts to Social Security and Medicare are on the table again,” Biden said Monday at a speech in New Hampshire following the release of his 2025 budget proposal. “I’m never going to allow that to happen.”

Opinion: The top 1% of Americans aren’t to blame for income inequality

“The belief that income inequality has risen sharply in the U.S. may be wrong.”

For decades, the share of national income held by the top 1% in the United States has soared. Income inequality, which former U.S. President Barack Obama declared “the defining challenge of our time,” has become a major issue in U.S. politics, with both Republicans and Democrats proposing higher taxes on the rich.

The idea, peddled by nationalists and progressives, that the economic system is rigged against ordinary workers and households has also fanned the flames of populism. Some even argue that economic inequality threatens democracy.

And yet, the belief that income inequality has risen sharply may be wrong. New research by Gerald Auten of the U.S. Treasury Department and David Splinter of the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation finds that the after-tax income share of the top 1% has barely changed since 1962. This stands in stark contrast to the work of Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, which has shaped policy and political debate in recent years: the trio conclude that the income share of the top 1% increased by roughly 55% over the same period.

Rather than answer the question of who is right (although I believe that Auten and Splinter are closer to the truth), it is more useful to consider whether the top 1% should be our focus. Seen from a broader perspective, the debate over income equality does little for those who need help the most.

The discussion has mostly centered on how much of the economic pie each group gets. But the size of the pie is not fixed. Since 1962, real economic output in the U.S. has increased by 499%, leading to significant improvements in living standards and human welfare. The percentage of Americans in poverty has decreased substantially, new medicines and therapies have greatly enhanced people’s quality of life, and more women have entered the workforce.

This considerable improvement in Americans’ well-being is more striking than the share of income accruing to the country’s highest earners. Compare a median-income U.S. household to one in the top 1%. Each has access to high-quality medical care and pharmaceuticals, each can take nice vacations, each can eat in the same restaurants, read the same books and watch the same television shows, and each has warm clothes and a comfortable home.

To be sure, there are disparities — the wealthier family has better health care, flies first-class to the Caribbean on holiday, occasionally eats at Michelin-starred restaurants, and has a bigger house. But this does not negate that inequality in quality of life has shrunk dramatically in recent decades. The quality-of-life gap between a median-income household and one in the top 1% a century ago, and even a century before that, was much larger.

Moreover, the economic and philosophical underpinnings of this obsession with the top 1% are far from sound. In a market economy, income is earned, not distributed. In a democracy, inequality is acceptable if it is driven by productivity differences — and the best evidence shows a strong link between pay and productivity in the U.S.

“How much ‘should’ the top earners ‘receive’ from society?”

Ultimately, the income-inequality debate is normative: How much “should” the top earners “receive” from society? It would be better to start from the premise that the wealthiest have earned their income, and to ask how much of these earnings should be taken by the government. According to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the top 1% earned 17.6% of all market income and paid 24.7% of all federal taxes in 2019, suggesting that they are already on the hook for quite a bit.

Ironically, concern about the income gap exploded during a period when, as I show in my book The American Dream Is Not Dead (But Populism Could Kill It), measured inequality was stagnant or declining. Using data from the CBO, I found that income inequality across all households — after accounting for taxes and government transfers and estimated with a Gini coefficient — increased by 29% between 1979 and 2007, but then fell by more than 5% between 2007 and 2019.

To understand this trend, one must focus on the bottom 99%. Even though inequality was rising in the 1990s, average wages were also increasing; Americans were not concerned about whether they were growing faster for some groups than for others. But after the 2008 financial crisis, average wages plummeted. In fact, they fell so sharply for the bottom half of workers that it took until 2014 for the median real wage to recover its 2007 level. This prolonged period of wage stagnation fomented anger and a sense of injustice, of a “rigged” economic game, which gave rise to populism.

The lesson is clear: People care about how they themselves are doing, and not about a group of people with whom they seldom interact. People are not as dripping with envy as the debate over inequality would have you think.

Anyone concerned about the health of American democracy should be more worried about wage growth for the bottom half of workers than the income gap. If upward mobility is the goal, then we must stop treating economic success as if it were a problem rather than something worth celebrating. Policymakers should focus on providing the poor and the working class with onramps to economic opportunity.

The 1% don’t deserve nearly as much attention as they receive. It would be better to concentrate on increasing the wages and incomes of those at the bottom, who are most in need of a helping hand.

Michael R. Strain, director of economic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, is the author, most recently, of The American Dream Is Not Dead (But Populism Could Kill It) (Templeton Press, 2020).

This commentary was published with the permission of Project Syndicate — The Myth of the 1%

More: This family just bumped Walmart’s Waltons as the richest in the world

Also read: The growing risk of global disorder

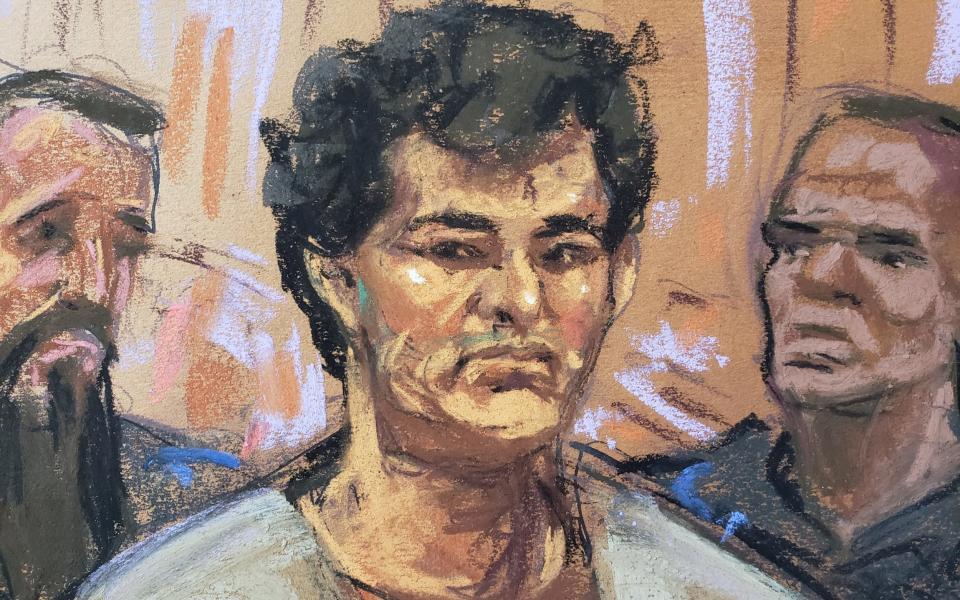

Crypto prodigy to ‘blame the lawyers’ in the fraud trial of the century

“I would like to start by formally stating, under oath: I f***** up,” wrote Sam Bankman-Fried, days after the implosion of FTX, the $36bn cryptocurrency exchange he founded.

The entrepreneur had hidden away in a $30m penthouse in the Bahamas, preparing a statement to justify his actions to US politicians.

Hours before he was due to give his evidence, Bankman-Fried was arrested by Bahamian police. Since then, he has had time – at home and more recently in a prison cell after his bail was revoked over allegations of witness tampering – to hone his line of defence.

In a courtroom in Manhattan next week, 11 months after the implosion of his digital currency empire, the 31-year-old former billionaire will face the cryptocurrency world’s trial of the century.

Bankman-Fried is charged by the US government with seven counts of conspiracy, fraud and money laundering at FTX – at one point the world’s second biggest digital coin exchange.

Prosecutors allege he misappropriated billions of dollars in FTX customer funds to finance risky bets at a crypto hedge fund – called Alameda – leaving an $8bn black hole and causing the company’s bankruptcy.

The trial is expected to last six weeks and he denies wrongdoing.

Former co-workers, roommates and ex-girlfriend, Caroline Ellison, are all expected to testify or provide evidence. Four former FTX executives, including Ellison, who led Alameda, have already pleaded guilty to separate fraud charges.

Bankman-Fried has argued he made mistakes, but never intended wrongdoing.

The trial will be closely watched by FTX’s one million creditors. Louise Abbott, a partner at Keystone Law which is representing claimants in separate bankruptcy proceedings, says: “Creditors want to see justice being done.”

Starting on Tuesday, Bankman-Fried’s defence will be weighed against the millions of pages of evidence, private messages and audio recordings that have been gathered by the US government.

According to legal papers submitted before the trial, Bankman-Fried’s lawyers will argue he was just doing what he had been told was legal – a so-called “advice of counsel” defence – or blame the lawyers.

FTX imploded last November in a matter of days after the missing billions in its accounts were revealed. John Ray, the bankruptcy expert who later took control of the business, called its corporate systems a “dumpster fire”.

The US prosecutors allege this was all as a result of Bankman-Fried’s failed money-making scheme. FTX secretly inflated the value of a cryptocurrency token it controlled, called FTT, that made up the majority of its assets, while using customer deposits to help Alameda borrow billions of dollars to fund trades – in violation of its own terms and conditions.

After a mass sell-off of FTT, the scheme unravelled.

Prosecutors argue Bankman-Fried masterminded these plans and used “billions of dollars in stolen funds” to buy up luxury property and donate to political campaigns.

Bankman-Fried has pleaded not guilty. In a letter disclosed to the court, Mark Cohen, Bankman-Fried’s lawyer, argues that FTX’s legal advisers, which included Silicon Valley law firm Fenwick & West, “gave him assurance he was acting in good faith” when he used apps that automatically deleted records at FTX and set up huge loans to company executives.

The letter named three other FTX lawyers involved in “approving decisions”. Meanwhile, Bankman-Fried has publicly criticised another law firm FTX used, Sullivan & Cromwell, for allegedly pressuring him into declaring bankruptcy. In the bankruptcy case, Sullivan & Cromwell called Mr Bankman-Fried’s claims “false”.

Fenwick & West and Sullivan & Cromwell did not respond to requests for comment.

Martin Auerbach, head of the white collar and investigations practice at the law firm Withersworldwide in New York, says Bankman-Fried is likely to try to show he had “surrounded himself with the best and brightest and paid them a lot of money” to advise him on the legality of his actions.

Typically, this also requires the defendant to provide evidence they had given their lawyers the information they needed to provide solid advice.

Bankman-Fried’s lawyers told the court the advice he received from legal advisers was “relevant to rebut” the government’s argument that he acted with criminal intent.

Within days of FTX’s failure ,Ellison, who led Bankman-Fried’s ostensibly separate crypto hedge fund, had signed a guilty plea agreement.

In July, the New York Times published excerpts from her private diaries, which a judge decided had likely been leaked by Bankman-Fried to “frighten” her.

After the leak, Bankman-Fried was returned to prison and his $250m bail revoked. Since then the former crypto prodigy has waited behind bars for his trial to begin.

For the prosecution, evidence related to Ellison could be crucial to proving “criminal conspiracy”, according to a court filing. Days before FTX failed, Ellison addressed staff.

Asked who had authorised taking money from FTX customers to fund its high-risk hedge fund, Ellison said: “Um… Sam I guess.”

Should he be found guilty, Bankman-Fried could sentenced to 115 years in prison.