The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has lowered Russia’s rating owing to insufficient oversight of cryptocurrencies, as indicated by regional coverage. According to RBC, this downgrade highlights escalating worries about the country’s capacity to oversee and mitigate dubious transactions within the rapidly expanding realm of digital finance. Russia’s Financial Strategy Challenged by FATF Downgrade The […]

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has lowered Russia’s rating owing to insufficient oversight of cryptocurrencies, as indicated by regional coverage. According to RBC, this downgrade highlights escalating worries about the country’s capacity to oversee and mitigate dubious transactions within the rapidly expanding realm of digital finance. Russia’s Financial Strategy Challenged by FATF Downgrade The […]

Source link

Russias

Chinese firms are playing an increasingly critical role in supplementing Russia’s struggling economy and boosting its military capabilities, including via the trade of goods for use on the battlefield in Ukraine, new analysis by CNBC shows.

Russian customs data filed as recently as August 2023 point to the continued import of drones, helmets, vests and radios from China, providing a lifeline for President Vladimir Putin’s over 18-month war of attrition, and a lucrative avenue for Chinese companies.

At the same time, the emergence of less widely documented Chinese exports that are ostensibly for civilian use, including vehicles, construction equipment and synthetic materials, are providing direct and indirect support to Russia’s war efforts, analysts told CNBC.

“I think there’s no question that the Chinese authorities are aware of the trade flows. They’re large enough that they could not continue without the acquiescence of the Chinese government,” Mark Cancian, senior advisor at Washington-based think tank the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said.

Russian President Vladimir Putin and China’s President Xi Jinping shake hands after delivering a joint statement following their talks at the Kremlin in Moscow on March 21, 2023.

Mikhail Tereshchenko | Afp | Getty Images

The defense ministries of China and Russia did not respond to CNBC’s request for comment on the trade flows.

This trade is happening despite insistence from Beijing that its trade with Moscow constitutes “normal economic cooperation” and that it targets no “third party.” Last week, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi confirmed China’s continued business cooperation with Russia ahead of a planned meeting between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese leader Xi Jinping in October.

The comments follow the release in July of a U.S. intelligence report stating that China “has also become an increasingly important buttress for Russia in its war effort, probably supplying Moscow with key technology and dual-use equipment used in Ukraine.”

Examples of goods supplied included navigation equipment, jamming technology and fight jet parts, it said.

Indeed, Kyiv has reported that its forces are increasingly finding Chinese components in weapons used by Russia’s military since April 2023 – the same month that Putin and Li Shangfu, the Chinese defense minister at the time, reiterated their countries’ “no limits partnership.”

Ukraine’s Defense Ministry and the general staff of the Ukrainian Armed Forces did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the battlefield findings.

Trade of ‘dual-use’ goods spikes

Total bilateral trade between Russia and China hit a record high of $190 billion in 2022, up 30% from 2021. This year is set to eclipse that figure, with total trade hitting $134 billion in the first seven months of 2023.

China now accounts for around half (45%-50%) of Russia’s imports, up from one-quarter before the war, according to estimates from the Bank of Finland’s Institute for Emerging Economies. That includes trade of so-called dual-use items and technologies – goods with both civilian and military applications, such as drones and microchips.

In 2022, China sold more than $500 million worth of semiconductors to Russia, up from $200 million in 2021. Meantime, China sold more than $12 million worth of drones to Russia in the year to March 2023.

Semiconductor sales to Russia from China and Hong Kong more than doubled in 2022 as Western sanctions took hold.

CNBC

CNBC analysis of Russian declarations and certificates of conformity filed to the Federal Accreditation Service — a prerequisite for the import and sale of goods in the country — showed the trade of such goods between Russian and Chinese companies from the onset of Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 to present. Such declarations are filed by the buyer rather than the maker of the goods.

Drones produced by Chinese multinational SZ DJI Technology were registered in Russia in unspecified volumes on various occasions between September 2022 and January 2023 — with imports stemming both directly from the company and indirectly from Chinese exporters including Shenzhen-based Autel Robotics and Iflight Technology — translated filings showed.

That is despite DJI issuing a statement on its website in April 2023, saying that it had “voluntarily suspended all sales to and business in both Russia and Ukraine as of April 26, 2022 and contractually forbid any sales by dealers to either country and for combat use.”

A DJI Inspire 1 Pro drone is flown during a demonstration at the SZ DJI Technology Co. headquarters in Shenzhen, China, on Wednesday, April 20, 2016.

Qilai Shen | Bloomberg | Getty Images

When contacted by CNBC, a DJI spokesperson said: “We take regulatory compliance very seriously, and we have taken all steps in our control to emphasize that our products should not be used in combat to cause harm or be modified to be turned into weapons.”

One of the importers of the drones, Moscow-based Nebesnaya Mekhanika, which roughly translates as “Heavenly Mechanics” and which, before the war, was DJI’s official distributor in Russia, submitted its filing in September 2022, the documents showed

Another importer, Moscow-based Vodukh, also registered an unspecified number of lithium ion and lithium polymer batteries and an unknown number of battery stations directly from DJI in Jul. 2023 and Nov. 2022, respectively, according to the records. Such items can be used to power goods ranging from small electronic devices to electric vehicles.

A third, Rostov-on-Don-registered Pozitron, additionally imported more than 54,000 helmets — either construction or military, according to the vague wording of the filing — from Chinese suppliers Liaoning B&R Technology and Beijing KRnatural International Trade Co in late 2022.

What we are seeing is that Chinese companies are selling to Russia what they maybe can’t sell in China or the West at a higher price.

Antonia Hmaidi

analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies

Defense analyst Cancian said it was apparent that such goods have been a critical facet of Russia’s military arsenal.

“They (Russia) have been firing, for example, artillery at the rate of 10,000 to even 20,000 rounds a day. To keep up that level of expenditure, they need to get some help from the outside,” he said.

“They also started running out of cruise missiles. Their stocks were pretty much exhausted within the first six months or so, so they’ve been able to manufacture additional cruise missiles with components provided by the Chinese,” he added.

Helmets and vests were also procured in batches of 100,000 each in Nov. 2022 from Shanghai-headquartered Deekon (Shanghai) Industry Co., a manufacturer of military products and police equipment, by Moscow-based Legittelecom, the documents showed.

Legittelecom, which, according to its website, provides consulting services on permits for the “import, export and sale of radio electronics and high-frequency devices,” also imported an unknown number of portable radios, or walkie-talkies, from wireless communications company Hong Kong Retekess in March 2023.

It was not clear from the documents if Legittelecom was the end user of the products, or to whom it was providing the permits, though Chinese-made radios have been recovered from Ukraine’s battlefield. The companies did not respond to CNBC’s request for comment on the transactions.

However, analysts said the irregular import patterns suggest there is opportunism among businesses on both sides as they seek to take advantage of Moscow’s military needs.

A Russian military radio produced by Chinese manufacturer Baofeng is displayed during an open-air exhibition of destroyed Russian military equipment and tactical gear on June 15, 2023 in Kyiv, Ukraine.

Global Images Ukraine | Getty Images

“What we are seeing is that Chinese companies are selling to Russia what they maybe can’t sell in China or the West at a higher price,” said Antonia Hmaidi, an analyst at Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies, who has been studying Chinese dual-use exports to Russia since the start of the war.

“It’s not the big exporters in China exporting this. Instead, it’s these small companies,” she continued, noting that the implications of Western sanctions targeting such companies would be minimal. “The companies, they don’t really have a lot of inherent value, which makes it quite easy to just open another one.”

Indeed, one company, Silva, was registered in the remote Eastern Siberian region of Buryatia in September 2022, and submitted import filings for 100,000 helmets from Shanghai H-Win New Material in March 2023. More recently, in August 2023, it filed for an unspecified number of radio telemetry systems, which can be used for tracking drones, from Hubei Jingzhou Mayatech Intelligent Technology.

Hmaidi cited another example of a Hong Kong company, established in 2020, which used to supply North Korea and has now added Russia to its books. Pyongyang, for its part, has been strengthening ties with Moscow, with the countries’ leaders meeting in Russia’s far eastern Amur region earlier this month amid Western suspicions that North Korea may be readying to provide Russia with war materiel.

CNBC contacted or attempted to contact all of the companies mentioned and received no response.

‘Underappreciated’ trade flows

As well as goods with overt military applications, Russia has also increased it imports of Chinese goods with potential direct and indirect war implications, according to analysts.

Chinese shipments to Russia of Aramid fiber, for instance, a class of heat-resistant synthetic fibers whose applications range from bicycle tires to bulletproof vests, rose more than 350% in dollar value terms in 2022 versus 2021, according to data compiled for CNBC by ImportGenius, a customs data aggregator. In January and February of 2023 alone, imports were close to 50% of 2022’s full-year total.

Meantime, construction equipment has played an “underappreciated” but significant role in China’s contribution to Russia’s war efforts, having helped bolster its defenses against Ukraine’s counteroffensive, Joseph Webster, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, said.

“Excavators and front-end shovel loaders are one of the most significant and frankly underappreciated aspects of China’s engagement with the war in Ukraine,” said Webster, who has studied the surge in such exports.

There was a massive increase in trench digging equipment to Russia … and that’s almost certainly not a coincidence.

Joseph Webster

senior fellow at the Atlantic Council

“There was a massive increase in trench digging equipment to Russia at a time when the Russian military forces were digging trenches. And that’s almost certainly not a coincidence,” he added.

Russian imports of Chinese earth-moving front-end shovel loaders were almost two times higher, and imports of excavators more than three times higher, in the first seven months of 2023 than during the same period a year prior, trade data showed.

Imports of Chinese heavy-duty trucks more broadly were up 11 times in value terms between January and May 2023 compared to the same period in 2021, with some identified on the battlefield and others used indirectly.

In June, a video featuring the head of Russia’s Chechen Republic, Ramzan Kadyrov, was shared on his official Telegram social media account. In it, he showcases various armored vehicles, including armored personnel carriers that appear to be Chinese “Tiger” vehicles, that he said were being deployed to Russia’s so-called special military operation in Ukraine.

A general view of the container terminal in Qianwan of Qingdao Port, a port in Shandong Province, China, March 17, 2023.

CFOTO | Future Publishing | Getty Images

“Even if the Chinese exports aren’t directly on the front lines, they’re still providing important economic assistance to Russia,” said Webster, suggesting that the added fleets could have significant implications in allowing Moscow to balance manufacturing output essential to both its civilian and military populations.

“Because Chinese truck exports have supplied the Russian civilian sector with trucks, Kamaz might be able to repurpose production lines for armored vehicles,” Webster said of Russia’s sanctioned, state-owned truck manufacturer.

Chinese government collusion?

The findings add to the growing list of Chinese goods and companies reported to be supplying Russia’s military, including state-owned enterprises.

The U.S.’s July intelligence report cited state-owned China Taly Aviation Technologies and China Poly Technologies among the companies found to be providing Kremlin-linked defense companies with parts, including for Mi-system helicopters found on the frontlines.

When asked to comment on the intelligence report and the trade of dual-use goods, China’s commerce ministry referred CNBC to its May response to a similar question, in which it dubbed its trading relationship with Russia as one based on “mutual respect and mutual benefit, in which both win.”

“The Chinese department in charge has made clear China’s position on the Ukraine issue on many occasions: China will not add fuel to the fire, let alone take advantage of (the situation),” the ministry added, according to a translation.

It follows prior comments from the foreign ministry in April, which said that China would “not provide weapons” to either side in the war, and that it would “control the exports of dual-use items in accordance with laws and regulations.”

It remains unclear to what extent Chinese authorities are aware of – or implicated in – the trade. The items being dual-use has thus far left enough room for deniability for China to avoid Western sanctions. Meanwhile, Washington and the EU have both been reluctant to accuse Beijing outright.

The White House’s National Security Council did not respond to a request for comment on the trade flows.

However, analysts noted that there is little indication that Beijing is taking actions to mitigate the sales.

Exporters in China who export to Russia are not going to receive penalties for doing so, so long as they don’t explicitly violate Western sanctions.

Joseph Webster

senior fellow at the Atlantic Council

“Exporters in China who export to Russia are not going to receive penalties for doing so, so long as they don’t explicitly violate Western sanctions and don’t provoke additional tensions with the West. So long as they can keep these exports quiet, they seem to be at little risk of provoking the ire of the Communist Party,” Webster said.

Still, continued alliance with Moscow could have significant long-term consequences for China’s slowing economy. Already, the U.S. and several Western allies have restricted the trade of certain sensitive technologies to China as part of a wider de-risking, or diversification, away from Beijing amid national security concerns.

“China would prefer for Russia not to lose, but they would prefer not to get involved,” Hmaidi said. “There could be arguments to send weapons, and there has been intelligence around maybe they want to send weapons. But also, they are very, very careful to stay below the sanctions.”

Western allies now face a difficult decision: either target individual sellers knowing the impact may be limited or take action against Beijing with potentially wider repercussions and risks of retaliation.

“If China were to openly support Russia, there would be huge ramifications for the totality of Beijing’s economic, political and security relationship with the Washington- and Brussels-led alliance of democracies,” Webster said.

— CNBC’s Evelyn Cheng and NBC’s Yuliya Talmazan contributed to this report.

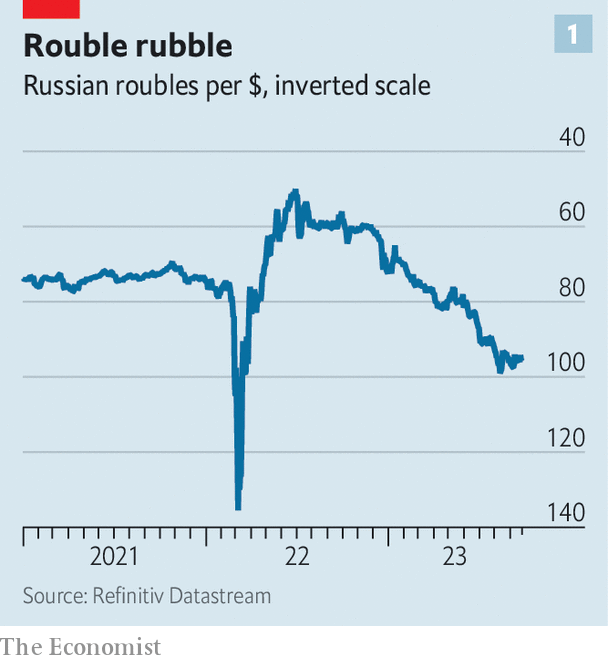

Over the past year few currencies have done worse than Russia’s rouble. Last September an American dollar bought just over 60 of them. These days it will buy almost 100 (see chart 1). The drop is both a symbolic blow to ordinary Russians, who equate a strong currency with a strong country, and the cause of tensions in the Russian state. It has blown apart the consensus that existed among Russian policymakers last year, when the central bank and finance ministry worked hand in glove. Now, as inflation rises and growth slows, the two institutions are turning against one another. At stake is the country’s ability to wage war effectively.

During the conflict’s early stages, Russian officials had a straightforward task: it was their job to stop the economy collapsing. Immediately after the invasion began, this involved preventing people from pulling money out of the financial system, by implementing capital controls and doubling the policy interest rate. The rouble hit 135 to the dollar, before recovering. The economy nosedived and then improved (see chart 2). Funded by juicy revenues from sales of oil and gas, the finance ministry then kept the show on the road by lavishing spending on defence and welfare.

Strong oil-and-gas exports also caused the rouble to appreciate, lowering import prices and in turn inflation. This allowed the central bank to accommodate fiscal expansion, cutting interest rates to below where they had been on the eve of the invasion. Over the course of 2022 consumer prices rose by 14% and real gdp declined by 2%—a weak performance, but miles better than forecasters had predicted. Last week Vladimir Putin noted that “the recovery stage for the Russian economy is finished”.

The new stage of the economic war presents officials with tough choices. Mindful of a presidential election in March, the finance ministry wants to support the economy. Bloomberg, a news service, has reported that Russia is planning to increase defence spending from 3.9% to 6% of gdp. The finance ministry also wants to raise social-security spending. Mr Putin is keen to run the economy hot. He recently boasted about Russia’s record-low unemployment rate, calling it “one of the most important indicators of the effectiveness of our entire economic policy” (conscription and emigration no doubt helped).

Yet the central bank is no longer keen to assist. The problem starts with the rouble. It is sliding in part because businessfolk are pulling money from the country. Low oil prices for much of this year have also cut the value of exports. Meanwhile, Russia has found new sources of everything from microchips to fizzy drinks. Resulting higher imports have raised demand for foreign currency, cutting the rouble’s value.

A falling currency is boosting Russian inflation, as the cost of these imports rises. So is the fiscal stimulus itself, warned Elvira Nabiullina, the central bank’s governor, in a recent statement. Consumer prices rose by 5.5% in the year to September, up from 4.3% in July. There are signs of “second-round” effects, in which inflation today leads to more tomorrow. Growth in nominal wages is more than 50% its pre-pandemic rate, even as productivity growth remains weak. Higher wages are adding to companies’ costs, and they are likely to pass them on in the form of higher prices. Inflation expectations are rising.

This has forced Ms Nabiullina to act. In August the central bank shocked markets, raising rates by 3.5 percentage points and then by another percentage point a month later. The hope is that higher rates entice foreign investors to buy roubles. Raising the cost of borrowing should also dampen domestic demand for imports.

But higher rates create problems for the finance ministry. Slower economic growth means more joblessness and smaller wage rises. Higher rates also raise borrowing costs, hitting mortgage-holders as well as the government itself. Last December the finance ministry decided it was a good idea to rely more heavily on variable-rate debt—just as borrowing costs began to rise. In August, conscious of higher rates, it then cancelled a planned auction of more debt.

Mr Putin would like to square the circle, defending the rouble without additional rate rises. He has therefore asked his policymakers to find creative solutions. Two main ideas are being explored: managing the currency and boosting energy exports. Neither looks likely to work.

Take the currency first. The government is keen to mandate exporters to give up more hard cash and make it harder for money to leave the country. In August officials started preparing “guidelines” that would “recommend” firms return not just sale proceeds but also dividend payments and overseas loans. On September 20th Alexei Moiseev, the deputy finance minister, hinted that capital controls were being considered to stem outflows to every country, even those deemed “friendly”.

Such measures are, at best, imperfect. Russia’s export industries form powerful lobbies. The experience of the past 18 months is that the firms which dominate energy, farming and mining are skilled at poking loopholes in currency controls, says Vladimir Milov, a deputy energy minister in the early days of Mr Putin’s reign. Waivers and exemptions abound. In late July Mr Putin issued a decree allowing exporters operating under intergovernmental agreements, which cover a big chunk of trade with China, Turkey and others, to keep proceeds offshore.

Civil war

The Kremlin also wants to create artificial demand for the rouble by forcing others to pay for Russia’s exports in the currency. Central bankers seem to think this plan is pretty stupid. “Contrary to popular belief,” as Ms Nabiullina noted in a speech on September 15th, the currency composition of export payments has no “notable impact” on exchange rates. The only thing that changes is the timing of the conversion. Either an exporter paid in dollars uses them to buy roubles, or the customer buys the roubles themselves. What might help Russia more would be to pay for more of its imports in domestic currency so as to save foreign exchange—and then for foreign sellers to keep hold of those roubles. But there is little sign of that happening.

Russia might consider using its foreign reserves to intervene in currency markets. Yet more than half of its $576bn-worth of reserves, held in the West, are frozen. Using the rest is hard because most of Russia’s institutions are under sanctions that limit their ability to conduct transactions, says Sofya Donets, a former Russian central-bank official. And the country’s available reserves, which have shrunk by 20% since before the war, could only defend the rouble for a little while anyway.

Short of raising rates, the only workable way to support the rouble is to boost energy exports. In theory, two factors are working in Russia’s favour. One is a rising oil price. Since July production cuts by Saudi Arabia and receding fears of a global recession have helped raise the price of Brent crude by nearly a third, to $97 a barrel. The other factor is a narrowing gap between the price of Urals, Russia’s flagship grade, and Brent, from $30 in January to $15 today (see chart 3). This gap is likely to continue to shrink. Since December members of the g7 have barred their shippers and insurers from helping to ferry the fuel to countries that still buy it unless it is sold under $60 a barrel. Russia’s response has been to build a “shadow” fleet of tankers, owned by middlemen in Asia and the Gulf, and to use state funds to insure shipments.

However, Russia’s oil-export proceeds will probably not rise more. Higher prices may depress consumption in America; China’s recovery from zero-covid seems over. Reid l’Anson of Kpler, a data firm, estimates that America, Brazil and Guyana could together increase output by 670,000 barrels a day next year, making up for two-thirds of Saudi Arabia’s current cuts. Futures markets suggest that prices will fall during much of 2024. Although Russia could export more oil to make up for this, doing so would accelerate the slide.

The other bad news for Russia is that it must now earn more from oil merely to keep its total export revenue flat, owing to declining gas sales after the closure of its main pipeline to Europe. In the fortnight to September 19th these were a paltry €73m ($77m), compared with €290m last year. There is talk in the eu of curbing imports of Russian liquefied natural gas. Europe’s nuclear-power generators are also cutting their dependence on Russian uranium.

All this means that, as Russia’s inflation troubles persist, the tussle between the government and the central bank will only intensify. The temptation to splurge ahead of the presidential vote next year will fan tensions, forcing the central bank either to crank up rates to debilitating levels or to give up the fight, leading to spiralling inflation. Alternatively, Mr Putin could cut military spending—but his plans for 2024 show he has little interest in doing that. The longer his war goes on, the more battles he will have to fight at home.

For more expert analysis of the biggest stories in economics, finance and markets, sign up to Money Talks, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.

© 2023 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved.

From The Economist, published under licence. The original content can be found on

How U.S. microchips are fueling Russia’s military — despite sanctions

Western microchips used to power smartphones and laptops are continuing to enter Russia and fuel its military arsenal, new analysis shows.

Trade data and manifests analyzed by CNBC show that Moscow has been sourcing an increased number of semiconductors and other advanced Western technologies through intermediary countries such as China.

In 2022, Russia imported $2.5 billion worth of semiconductor technologies, up from $1.8 billion in 2021.

Semiconductors and microchips play a crucial role in modern-day warfare, powering a range of equipment including drones, radios, missiles and armored vehicles.

The sanctions evasion and avoidance is surprisingly brazen at the moment.

Elina Ribakova

senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics

Indeed, the KSE Institute — an analytical center at the Kyiv School of Economics — recently analyzed 58 pieces of critical Russian military equipment recovered from Ukraine’s battlefield and found more than 1,000 foreign components, primarily Western semiconductor technologies.

Many of these components are subject to export controls. But, according to analysts CNBC spoke to, convoluted trade routes via China, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and elsewhere mean they are still entering Russia, adding to the country’s prewar stockpiles.

A collection of 58 pieces of Russian weaponry captured from the battlefield in Ukraine, such and drones and missiles, contained more than 1,000 Western components, according to a study from the KSE Institute.

CNBC

“Russia is still being able to import all the necessary Western-produced critical components for its military,” said Elina Ribakova, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, and one of the authors of KSE Institute’s report.

“The sanctions evasion and avoidance is surprisingly brazen at the moment,” she added.

Murky supply chains

Not all advanced technologies are subject to Western sanctions on Russia.

Many are dubbed dual-use items, meaning they have both civilian and military applications, and therefore fall outside of the scope of targeted export controls. A microchip may have applications in both a washing machine and a drone, for instance.

Still, many of these products originate from Western nations with sweeping trade bans against Moscow and, specifically, its military. All U.S.-origin items except food and medicine are prohibited from reaching Russia’s army.

It’s difficult to stop strictly civilian microelectronics from crossing borders.

Sam Bendett

advisor at the Center for Navel Analyses

In KSE’s study, more than two-thirds of the foreign components identified in Russian military equipment ultimately originated from companies headquartered in the U.S., with others coming from Ukrainian allies including Japan and Germany.

CNBC was unable to verify whether the implicated companies were aware of the final destination of their goods. Swiss authorities said they were working with firms to “educate them on red flags,” while government spokespeople for the other countries cited did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Separately, a study from the Royal United Services Institute found that Russia’s military uses over 450 different types of foreign-made components in its 27 most modern military systems, including cruise missiles, communications systems and electronic warfare complexes. Many of these parts are made by well-known U.S. companies that create microelectronics for the U.S. military.

More than two-thirds of tech elements recovered in KSE Institute’s study originated from companies headquartered in the U.S.

CNBC

“Over decades, non-Russian high-tech systems and technologies became more advanced and really have become industry and global standards. So, a Russian military, as well as its civilian economy, have become dependent,” Sam Bendett, advisor at the Center for Naval Analyses, said.

The ubiquity and wide-reaching applications of such technologies have led them to become intertwined in global supply chains and therefore harder to police. Meanwhile, sanctions on Russia are largely limited to Ukraine’s Western allies, meaning that many countries continue to trade with Russia.

“It’s difficult to stop strictly civilian microelectronics from crossing borders and from taking place in global trade. And this is what the Russian industry as well as the Russian military and its intelligence services are taking advantage of,” Bendett said.

Russia-China trade spikes

Those trade flows can be messy. Typically, a shipment may be sold and resold several times, often through legitimate businesses, before eventually reaching a neutral intermediary country, where it can then be sold to Russia.

Data suggests China is by far the largest exporter to Russia of microchips and other technology found in crucial battlefield items.

Sellers from China, including Hong Kong, accounted for more than 87% of total Russian semiconductor imports in the fourth quarter of 2022, compared with 33% in Q4 2021. More than half (55%) of those goods were not manufactured in China, but instead produced elsewhere and shipped to Russia via China and Hong Kong-based intermediaries.

China is really trying to accumulate and to make profits and gains on the fact that Russia is economically isolated.

“This should not be taken as a surprise because China is really trying to accumulate and to make profits and gains on the fact that Russia is economically isolated,” Olena Yurchenko, advisor at the Economic Security Council of Ukraine, said.

China’s trade department did not respond to a request for comment on the findings, nor did the Russian government.

Meantime, Moscow has also increased its imports from so-called intermediary countries in the Caucasus, Central Asia and the Middle East, according to national trade data.

Exports to Russia from Central Asia and Caucasus countries has increased significantly since Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, trade data shows.

CNBC

“A lot of these countries really cannot sever certain types of trade with Russia, especially those nations which are either bordering Russia, like Georgia, for example … as well as nations in Central Asia, which maintain a very significant trade balance with the Russian Federation,” Bendett said.

The governments of Georgia, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan did not respond to CNBC’s request for comment on the increase in trade.

Sanctions clampdown

The burgeoning trade flows have prompted calls from Western allies to either get more countries on board with sanctions, or slap secondary sanctions on certain entities operating within those countries in a bid to stifle Russia’s military strength.

In June 2023, the European Union adopted a new package of sanctions which includes an anti-circumvention tool to restrict the “sale, supply, transfer or export” of specified sanctioned goods and technology to certain third countries acting as intermediaries for Russia.

The package also added 87 new companies in countries spanning China, the United Arab Emirates and Armenia to the list of those directly supporting Russia’s military, and restricted the export of 15 technological items found in Russian military equipment in Ukraine.

If we have certain moral values … we cannot be giving [to Ukraine] with one hand and then giving to Russia with the other.

Elina Ribakova

senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics

“We are not sanctioning these countries themselves. What we are doing is preventing an already sanctioned product, which should not reach Russia, from reaching Russia through a third country,” EU spokesperson Daniel Ferrie said.

However, some are skeptical that the measures go far enough — particularly when it comes to major global trade partners.

“[The sanctions] may work against, let’s say, Armenia or Georgia, which are not big trade partners for European Union or for the United States. But in when it comes, for instance, to China or to Turkey, that’s a very unlikely scenario,” Yurchenko, of the Economic Security Council of Ukraine, said.

Others say that responsibility ultimately lies with the companies, which need to do more to monitor their supply chains and avoid their goods falling into the wrong hands.

“The companies themselves should have the infrastructure to be able to track it and comply with export controls,” Ribakova said.

“If we have certain moral values or national security objectives, we cannot be giving [to Ukraine] with one hand and then giving to Russia with the other.”

Russia’s economy dealt a crushing blow as its current-account surplus collapses by 93%

-

Russia’s current-account balance has collapsed, marking another blow to the floundering economy.

-

Surplus tanked 93% to $5.4 billion last quarter from a year before, according to the Bank of Russia.

-

That comes as Western sanctions continue to squeeze Russia’s oil and gas exports.

Russia’s economic woes are worsening, with the latest blow coming from a collapse in its current account.

The nation posted a current-account surplus of $5.4 billion for the April-June quarter, which marks a 93% plunge from a record $76.7 billion in the same period last year, Bank of Russia data shows. That’s also the smallest excess since the third quarter of 2020.

It shows the heavy blow that Western economic sanctions — imposed on the Kremlin in response to its war on Ukraine — have dealt to the country’s economy by squeezing its energy exports.

The worsening trade dynamics are also reflected in the plunging fortunes of the ruble. The Russian currency tumbled to a 15-month low of about 94.48 for each dollar earlier in July, hit hard by the country’s weakening terms of trade.

“The decline in the surplus of the balance of the external trade in goods in January — June 2023 compared to the comparable period of 2022 was caused by a decrease in both the physical volumes of export deliveries and the deterioration in the price situation for the basic Russian export commodities, energy commodities made the most significant contribution to the decline in the value of exports,” the Bank of Russia said.

Moscow’s key source of revenue is through sales of its oil and gas products, but price caps and bans imposed on Russia’s energy exports following its unprecedented attack on Ukraine have dealt a huge hit to its commodities business.

In June, Russia’s Finance Ministry said that revenue from oil and gas taxes fell 36% compared to a year ago to about 570.7 billion rubles and that profits from crude and petroleum products tumbled 31% to 425.7 billion rubles.

Market commentators have weighed in on Russia’s battered economy, with Yale researchers accusing President Vladimir Putin of cannibalizing the nation’s economy in his mission to seize Ukraine.

Read the original article on Business Insider