Few companies grow at above-average rates for more than a year or two. Or, as the late British economist and philosopher John Maynard Keynes famously put it, trees don’t grow to the sky.

This is especially important to remember now, with exuberant investors giving huge valuations to certain tech stocks. The poster child of such valuations is Nvidia

NVDA,

which recently sported a trailing 12-month P/E of 212 (compared to 20 for the S&P 500

SPX,

), a price-to-book ratio of 41 (versus 4.3 for the S&P 500) and a price-to-sales ratio of 39 (versus 2.5 for the S&P 500).

It’s most unlikely that Nvidia can live up to the growth assumptions embedded in these ratios. Consider a seminal study from two decades ago entitled “The Level and Persistence of Growth Rates,” conducted by Louis K. C. Chan and Josef Lakonishok of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Jason Karceski of LSV Asset Management. The researchers analyzed all publicly traded U.S. stocks back to the 1950s, searching for those that had above-median sales growth for several years in a row.

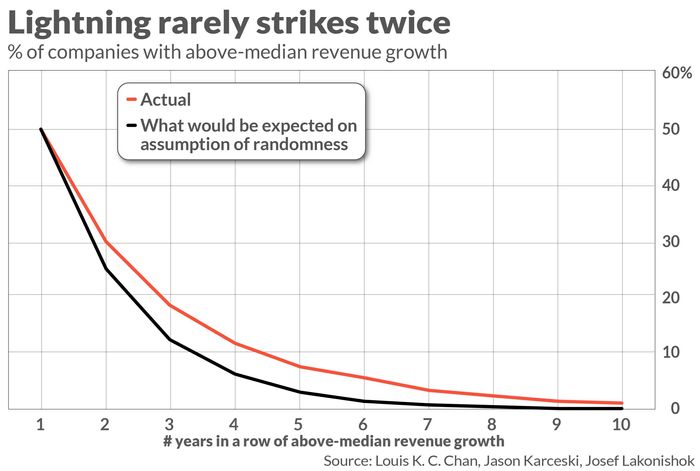

Their findings are summarized in the table below. The red line shows the percentage of companies with above-median sales growth for the indicated number of years in a row, while the black line reflects what the red line’s shape would be on the assumption of pure chance. Notice how close the two lines are to each other.

Some have tried to dismiss this two-decade-old study, arguing that the shift to a digital economy means that the historical data are irrelevant to today’s markets. But that argument is not persuasive, according to a study from last fall by Verdad Research. The firm applied the Chan/Lakonishok/Karceski methodology to stocks’ performance over the 20+ years since that study was completed, reaching nearly identical results.

Nvidia’s valuation

These results raise serious doubts about growth stocks’ higher P/E ratios. If we look backwards, we of course will see that growth stocks have been growing at a faster pace than value stocks. That’s why they’re growth stocks, after all. But, looking forward, their higher P/E ratios would be justified only if their historically fast growth rates persisted into the future. But that’s precisely what this research questions.

Consider the P/Es of the Vanguard Growth ETF

VUG,

and Vanguard Value ETF

VTV,

The recent P/E of the former ETF is more than twice that of the latter, according to Vanguard: 34.2 vs. 15.8. That reflects a big bet on the part of investors that growth stocks’ above-average growth rates will continue. This research suggests that’s a highly risky bet.

To illustrate, consider Nvidia. Its price-to-sales ratio (PSR) is nearly 10 times the 4.7 median PSR of stocks in the ICE Semiconductor Industry Index. If we assume that Nvidia’s PSR will eventually fall to match that of the median stock in that index, we can calculate the revenue growth that is necessary.

Let’s say it takes 10 years for Nvidia’s PSR to fall to that median, and that its stock over the next ten years appreciates at a 10% annualized rate. Both are generous assumptions; the half-life of a company’s above-average PSR is usually a lot less than 10 years, and investors almost certainly are hoping for a greater-than-10% annualized return to compensate them for the above-average risk of owning Nvidia shares. Nevertheless, to live up to these generous assumptions, Nvidia’s revenue will have to grow at a 23% annualized rate for the next 10 years.

You can see from the chart how unlikely that is. Bear in mind, furthermore, that the low odds plotted in the chart reflect the proportion of companies whose annual revenue growth is above the median. That’s a relatively low bar; the median according to the two-decade-ago study was around 6%. That means that, in order to live up to its current valuation, Nvidia’s revenue growth over the next 10 years must be almost four times the median annual historical rate. Is that how you want to bet?

Growth at what price?

Am I being overly pessimistic? Perhaps, according to Jay Ritter, a finance professor at the University of Florida. But not by a lot.

In an interview, Ritter pointed out that even though the odds of sustained above-median growth are low, they aren’t zero. And tech companies are more likely to produce such growth than non-tech companies, since “many tech companies have products that cannot be easily replicated and/or have low marginal costs. At the opposite extreme are companies in the restaurant industry or other industries with high marginal costs and no significant barriers to entry.”

Nevertheless, Ritter added, the odds of even a high-tech company living up to its high valuation are still low. “Almost everything must go right in order to avoid disappointing investors.”

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: The Nasdaq-100 is headed for its best first half on record. But the rally faces a high-stakes test in July.

Plus: Investors are pouring money into this modified S&P 500 stock-market strategy